Guest Blog: Ian Jeffrey - Middle England Revisited

On the eve of Photo London, Ian Jeffrey has very kindly given us permission to publish in full this wonderful piece he wrote about John's work for the occasion of his exhibition at Ikon in Birmingham 2011-12. This piece was originally published in the catalogue of that exhibition.

Ian's letter covers John's full body of work, the first part of which is available as The Portraits from RRB. The second volume, which contains the much lauded Televisions series, is to be titled Looking At The Overlooked, and will be published at the end of this year.

Letter from Ian Jeffrey, 18 October, 2011

In September 1975 The Royal Photographic Society Journal published a review of the book British Image 1, an anthology of work by eight young British photographers including John Myers, Homer Sykes, Daniel Meadows, Paul Carter and Claire Schwob. In the review, its author, the noted critic and art historian Ian Jeffrey, suggested that Myers used photography “as a form of language with traditional pictorial ideological needs just as the Dadaists worked with traditional forms to discredit those forms and the social order which they expressed.” Myers’ images, he wrote, along with those of other photographers included in the book, constituted “a sort of critical realism by exploiting the documentary mode for its pictorial properties and drawing on the credit of its authenticity.” John Myers recently wrote to Ian Jeffrey, asking him to look again at the work.

Dear John,

Thank you for the pictures, and for the news of the forthcoming exhibition.

What do I make of them now? A lot of the new British photography of the 1970s was marketed under a sociological heading – classified as documentary and put away, put to one side. It was, I recall a great age of social study, of organization men and Levittowners. Sociology provided a prism and a grid, a way of understanding. I think, though, that it led to a culture of low expectations – certainly on my part. Maybe I took the official line too seriously, even though I would have denied it at the time. I took the sociological rubric too seriously, and would have seen your pictures as studies of British citizenry during an age of transition, marked by the arrival of TV and supermarkets – say.

Looking at your pictures now hardly a single sociological thought crosses my mind. I notice, I suppose, how manners have changed and how interior décor has altered, but those are only incidentals. It was a great period for electric fires – so very convenient. There is a lot of satisfaction to be had from looking at ornaments, carpet slippers, clock faces, floral patterning. Does the plate on the patterned wallpaper feature Drake at Plymouth Ho – they seem to be playing bowls? Are those the Hollies on the wall of that untidy bedroom? At this range I can’t read the fine details. Mr. Seabourne’s posture, smoking his pipe on the couch, does remind me of Harold Wilson, and the ginger jar and carved elephant are of the period. There are forensic details, too, such as the bolt on the outside of the door in the portrait of the girl with the hood. It can’t have been a lavatory, as I first thought.

Ridiculous musings, you might think. I don’t know. Take the giraffe, for example, nuzzling its midriff. Those might be radiators around its enclosure – of the old hospital style. You would have to keep giraffes warm, because they are tropical beasts, and you would have to warm them at body level, which is quite high up – just as you would have to feed them at head level –high up as well. Giraffe keepers would have to take such things into account. So, the giraffe study makes up an empathy picture – like a lot of other photographs. The tiny infant on the couch could also wriggle and fall off, or even gets its leg stuck in the interval between the cushions. I am alerted that is to say, to a predicament, a possibility of things going wrong. The girl with the hood is another case in point. I can easily imagine what it would be like to stand with my ankles pressed so close together, and think of the difficulties of getting one’s hands through the slots in case of an emergency. The staggered brickwork in the embrasure in the second picture makes a dislocated rhyme with the oval fur of her hood and that also reminds me of what it might feel like to knock my head on one of those projections. The youth holding up the dead pig would also have had to watch out for drops of body fluid falling on to his clothes, his feet and ankles especially. He has rolled his overalls up for a purpose. Maybe the rolling is to make a ridge to protect his trousers? You will agree that remarks like this don’t amount to the heavy duty materials of photo-criticism.

However I think that I am on to something. Take the picture of the girl in the long skirt [Andrea and monsteria] standing in front of that potted palm beside a couch. I’ve sat on couches like that, on just that kind of velveteen (?) cushion and traced the patterns with my fingers – labyrinthine and a bit prickly to the touch. That is a fine plant as well, its leaves like tractor seats, big and metallic. She has a frieze of monkey-like cats on her sweater – or maybe cat-like monkeys. There is an early H.C.-B. [Henri Cartier-Bresson] of a man in a street in Madrid: a man in a bowler hat turning towards the camera against a background of pruned trees, meant to stand in for a fractured mind. H.C.-B.’s is a trope for the man and his imagined mind. Your picture is something like that, but more like innocence abroad in a garden of frightening possibilities. I was reminded of the early portraits of Lucian Freud, especially that one of the man in a macintosh, now in Liverpool. The carpet there is rucked up and something of a danger. The potted palm in that instance is on the way to dying, certainly not looking good. Thee standing man holds a cigarette in his left hand, but has his nicotine stains on his right. He has been encumbered, or put in an awkward situation. He sees, for example, but like us he sees the conspicuously fading palm, and is forever kept from lighting up.

What am I getting at? Your pictures suggest to me that they should be read as pictures, with deliberation – hence the reminder of Lucian Freud. They have iconography, even if not quite in the sense that there is iconography of the Passion – with its instruments, nails, pliers, hammers and so on. What you usually do (I’m looking at the portraits) is to show a restricted setting with a few things on show. I like the picture of the man [Percy] in the overcoat with the trimmed tree trunks – sycamores possibly. He has a hat, a tie and a handkerchief in his breast pocket, and there are those sparse items in the background against the brick wall. You could itemise the contents and even count the bricks, even though they are an erratic system – or non-system. Atget usually makes an invitation to count and classify, and it implies significance, this process. The man in the overcoat is definitely in a system of some sort, familiar items which look as if they might make sense. The man on the kaleidoscope couch [Robert], by contrast, lives in an environment of mazy intricacies – the couch fabric looks positively ocean-going. The man next to him [Richard Smith] in the set of pictures you sent me, sits on an Edgerton-style carpet, whooshing diagonally through the picture space towards a curtain of giant raindrops ponderously falling. If we wait long enough the huge lampshade might fall and engulf your subject. Everything is nicely and kinetically judged: the whizzing carpet, those organic globules and the dignified doorway – a kinetic arrangement, with the subject ready to be swept along, distracted by the act of portraiture.

Each picture is different, although they all touch on the human condition, which, in this case is a challenged and threatening position. The man in the shiny boots might, in his dynamised setting, be swept away on that fast moving carpet. The man [Robert] on the ocean-going couch might be bamboozled by the intricacies he seems to have got himself into, or even devised for himself. I like the picture of the juvenile soccer player [Young Boy with ball] a sort of proto-Johann Cruyff, faced by a variety of possibilities: principally the labyrinthine pitch on which he stands, along with the portal and grid on the wall. I like, too, that other somewhat gloomy girl on the couch. [Woman in striped dress] The radiator in a perfunctory way, spells warmth and the couch comfort. The pack of cigarettes and the ashtray by her side point to another in a restricted set of options. The dress is another labyrinthine motif. She looks like a demotic refugee from the land of Diane Arbus, but I appreciate her more ordinary placing, and can identify with its everyday range. Her neighbour, in the set that you sent me, the girl [Vanessa] with the white yoke and (again) shiny boots seems to have got herself into an odd situation: behind her a carpet tacked onto the wall, maybe because it was too big for the space – and rolled up it would have encroached on the floor area. I am asked to reflect on just what sort of room it is, and what kind of decisions had to be taken by whoever to put it to rights.

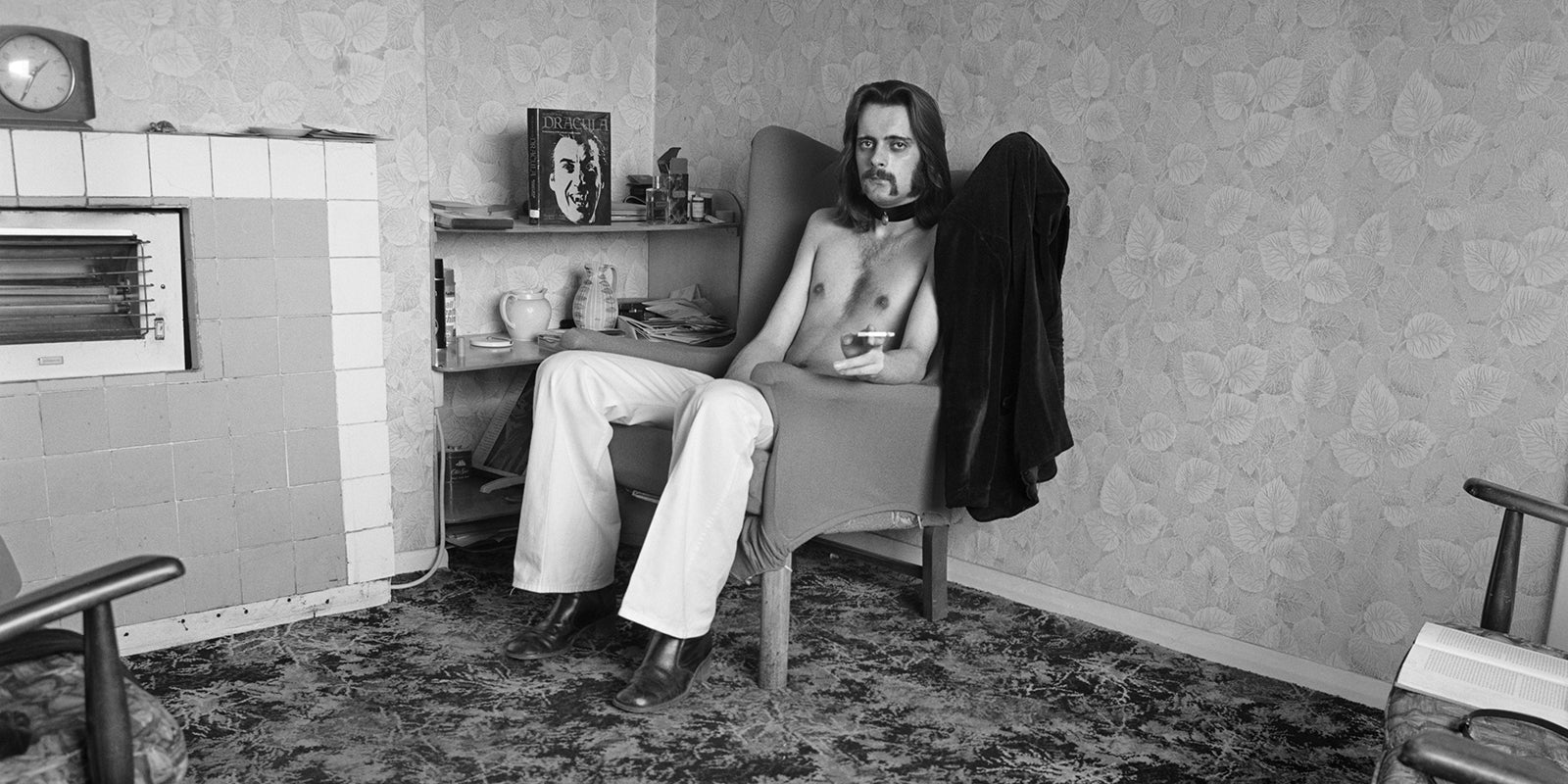

The human condition, did I say? Well, up to a point. That Santa Claus in his makeshift beard, which looks like it has been made from shaving foam, isn’t going to convince anyone, but at the same time how diverting to see what looks like a full of washing powders: Omo, Surf, Ariel and Persil. What I have to take account of, all the time, is the author’s choice. I am asked to notice it, and even do a bit of working out in a speculative way. There’s that Charles Manson figure, [John] for instance, sat in the corner of the room. Is he meant to have wings, like an angel of death? Is he meant to take the saturnine part in relation to that jovial portrait on the bookcase?

Artist’s intentions? The pictures come in several sets: portraits, landscapes, buildings (substations). I tend to see them as part of a larger project. Take the ‘Landscapes without Incident, for example, which are as empty as the title promises. But it is not entirely a pure emptiness, for all the pictures show spaces about to be occupied or quitted. The 7 garages from 1975 look like traps at a race meeting – for saloon cars maybe. The dual carriage-way is an exaggeratedly fast space, haring towards its distant vanishing point. The brick block of 1979 [Multi-storey car park] looks like a destination, waiting to be occupied. The golf course, with its flag flying, is a transit zone, and Heath Lane has nice intersecting dynamics borne out by the speeding children on the warning sign. The garden picture [Benjamin the Rabbit] is another destination waiting its occupants. Tree of Heaven ‘ I couldn’t quite work out but it is certainly aspiring in bleak surroundings – a relative of some of Sudek’s garden fruit trees. The two instances of Ring Road Gardens’ look as if they might epitomise suburban bleakness but I see both as dynamised: the cement owls mark out and complement the orthogonals in the rapid system of perspective, and in No. 2 it looks as if a rush of rocks and gravel has been brought up short by that deeply angled wall.

You might argue that you simply have a sense of the dynamic or of onrush and that you indulge that sense as you register something else. I would say, though, that it is a sense which is crucial to your aesthetic. The people in the portraits exist in spaces which they may find hard to cope with. The ballet girl, for instance, seems to be involved in a kind of endless mirroring, a mis en abyme. The cactus boy is awkwardly pressed on, in addition to not knowing quite what to do with his hands. Spaces zoom away, or they act lumpish, or they baffle by their variety and complexity, usually represented by complex patterns in wallpaper and carpeting. The substations are, of course, common-places in the British landscape, in roughly trimmed and gritted grounds. They look, if one cares to look at them, like mysterious destinations, terminal points, often windowless. They function as stoppages in the play of energy which you register in the other pictures. The furniture showrooms, also early on (1974) imply stasis, a journey’s end of idealised conversation in maximum physical comfort – debilitating comfort I would say.

Once I get the hang of the dynamics of the landscapes I can see how the houses are intended. Looking in isolation, in an estate agent’s window, I might read them as nothing more than houses (fetish objects worth so much), but looked at in this context I begin to understand them as habitable spaces accessed by light through transparent screens and by automobiles through carports. They look like points of convergence because of the roads rather than tracks which lead up to them – and quite a number of these roads/drives are on a slope or at an angle. They are part, that is to say, of that same dynamised environment which tests the residents.

The TV screens I see as part of a social project, for they are legible in terms of their placing and furnishings – book collections in particular. Symptomatic montages, I might call them. They have least to do with their author, I think, and a lot to do with lifestyles. I suppose that in the larger scheme of things they have an occulist quality and feature as the live centre of the mileu you have been describing in the 1970s. In several of them you appear, I see, as a crouching acolyte.

Thank you again. I very much enjoyed myself.

Ian